Taking a Closer Look at Myotubular Myopathy

A range of outcomes

When Patrick and Sarah Foye of Pine Brook, N.J., had their baby boy, Adam, in 2001, there was little reason to believe at first that anything was wrong. "Adam had a normal birth," Sarah says, but things didn't go as well as expected in the months that followed.

Patrick is a physician specializing in rehabilitation, and Sarah is an occupational therapist, so they were quick to note that something wasn’t right, even though Adam was their first child.

Missing milestones

"He wasn't meeting the normal motor milestones, the first one being head control," Sarah recalls. "At six months, we started the evaluation process."

There was no history of neuromuscular disease in either her family or Patrick’s, but because of Patrick’s staff position at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey in Newark, they soon found themselves at that center’s MDA clinic.

There, clinic co-director Jennifer Michaels ordered a muscle biopsy for Adam. At 13 months, they had a diagnosis: myotubular myopathy (MTM), a muscle disease affecting males almost exclusively and involving severe weakness, respiratory insufficiency, and often, early death. An alternate name for it, they learned, was centronuclear myopathy, or CNM.

Immature fibers?

In 1997, mutations (flaws) in the X chromosome gene for a protein that became known as myotubularin were identified as a cause of this disorder, but the disease had been recognized for decades.

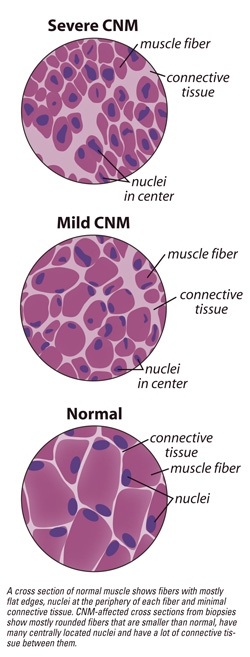

Back in 1966, doctors at the University of Pennsylvania had proposed that it resulted from a failure of muscle fibers to mature. Immature fibers, called myotubes, have nuclei in their centers instead of around the periphery, as mature fibers do. In MTM, the fibers look more like fetal myotubes than mature muscle fibers. (The immature fiber hypothesis is still around today, but few believe the explanation for MTM is that simple.)

A typical 6-year-old

Adam survived his infancy, learned to sit up at about 9 months (on the late side) and to walk at 15 months (well within the normal range), but he didn’t start crawling until 20 months (most babies master that by 14 months), and he still has trouble controlling his head if he’s pulled from a lying to a sitting position. He also has a weak cough and is prone to respiratory infections.

Adam survived his infancy, learned to sit up at about 9 months (on the late side) and to walk at 15 months (well within the normal range), but he didn’t start crawling until 20 months (most babies master that by 14 months), and he still has trouble controlling his head if he’s pulled from a lying to a sitting position. He also has a weak cough and is prone to respiratory infections.

Clearly, though, there never was anything wrong with Adam’s brain. “He always had precocious, advanced language skills,” Patrick says. “He was always very bright. It was just a matter of trying to nurture all of that as much as possible. Most children learn by exploring their environment, but Adam didn’t have the motor skills to crawl or walk or even just pull something over to him.”

These days, with the help of his parents, a physical therapist, a few adaptations and dedicated teachers in the public school he attends, Adam is “in many ways, just a typical 6-year-old boy,” his father says. He loves volcanoes, dinosaurs, drawing, reading and even playing T-ball, although he moves more slowly than other children his age.

The Foyes, however, haven’t stopped trying to get to the bottom of Adam’s muscle disease. A little more than a year ago, they began taking part in genetic research studies being conducted by Alan Beggs, an MDA grantee at Children’s Hospital in Boston.

“If you had asked us in March of last year, we would have said Adam’s diagnosis was myotubular myopathy,” Patrick Foye says. But, after meeting with Beggs, they don’t use that term anymore.

Changing terminology reflects new understanding

“Centronuclear myopathy is an umbrella term to encompass a group of similar congenital myopathies in which the only signifi-cant finding on muscle biopsy is centrally placed nuclei, and physical findings are a patient with otherwise unexplained weakness or lack of muscle tone,” Beggs says.

“That can include patients who are so weak that they die of respiratory insufficiency in the first year of life, and at the other end of spectrum, it can include people who aren’t quite sure that they even have a genetic disorder and who grow up to have children of their own.”

In 2005, Beggs was part of a multinational research team that identified mutations in the gene for a protein called dynamin 2 as an additional cause of CNM and an explanation for at least some people who had this disease but didn’t have myotubularin defects. (Adam’s test for myotubularin mutations was negative.)

Beggs’ group, along with prominent muscle specialists in France, began proposing that MTM be reserved for the X-linked form of CNM, which is usually (though not always) quite severe and often fatal; and that other forms of CNM, of varying severity, be classified according to their genetic origin.

Mutations in the dynamin 2 gene, on chromosome 19, seem to cause a relatively mild, late-onset form of CNM. This form of CNM, which has been seen in 11 families, is autosomal dominant, meaning it’s not X-linked and that only one flawed gene is sufficient to cause symptoms.

In addition, one person has been identified as having moderately severe CNM related to a mutation in the MYF6 gene, on chromosome 12. And recently, a 16-year-old girl with CNM-like symptoms was found to have a mutation in another chromosome 19 gene, RYR1, suggesting that at least two other forms of autosomal dominant CNM may exist. The teenager’s disease had progressed slowly, but she was no longer able to stand alone and had significant weakness in her chewing, swallowing and eye movement muscles, as well as respiratory muscle weakness.

However, many patients, like Adam, appear to have an autosomal recessive form of CNM, one that's not X-linked and re-quires two flawed genes (one from each parent) before symptoms appear. This form tends to show up in early childhood but often isn't as severe as the X-linked MTM form.

However, many patients, like Adam, appear to have an autosomal recessive form of CNM, one that's not X-linked and re-quires two flawed genes (one from each parent) before symptoms appear. This form tends to show up in early childhood but often isn't as severe as the X-linked MTM form.

What ties all these disorders together is the presence of centrally located nuclei in the muscle fibers, a finding that's re-vealed when a biopsy sample is examined.

Unfortunately, Beggs says, the typical pathologist looks at the muscle, sees central nuclei, and if the patient is a baby, will call it myotubular myopathy. "Then," he says, "the geneticist or neurologist looks up myotubular myopathy, sees that it's associated with death at an early age, and that's what the family is told. In some cases, though, the child actually has a milder form of centronuclear myopathy. They're told to expect the worst, and then that doesn't happen."

Beggs' group has found that, in general, genetic mutations that allow production of relatively normal myotubularin and muscle fibers as large as or larger than normal predict a more favorable outcome than mutations that lead to highly abnormal myotubularin and small fibers.

He would prefer that families be told that "there is a range of outcomes, and we have to warn you that many cases result in early death. However, you should have hope for the future and be aggressive in treating your child."

A close call

Although the prognosis for many people with CNM who survive infancy has brightened considerably in recent years, it can still be a serious, even life-threatening, condition.

Surgery and anesthesia are among the most serious stresses for people with CNM and other myopathies that affect the respiratory muscles. They need close monitoring before and during an operation.

Ray Santa Lucia of Saddle Brook, N.J., who, like Adam Foye, probably has an autosomal recessive CNM, learned this the hard way.

At age 2, doctors diagnosed MTM, based on a biopsy, but the grim prognosis that label carries fortunately proved inaccurate. Santa Lucia, now 34, survived early childhood and, by the time he started school, was walking well, if not running. He was strong enough to play outfield positions in Little League. "I did as much as I could," Santa Lucia says. "On the playground, I always played the easiest position. For kickball, I would be the one throwing the ball, not running after it."

His mental development was above average. He was a good student, graduating third in his high school class of 150, and won a lot of chess tournaments. "I was a brainy, workaholic, nerdy kid," he says.

His mental development was above average. He was a good student, graduating third in his high school class of 150, and won a lot of chess tournaments. "I was a brainy, workaholic, nerdy kid," he says.

After graduating from college and traveling through Europe on his own, Santa Lucia entered graduate school at the University of South Florida in Tampa, where he earned a doctorate in clinical psychology in 2004.

Things were going so well that there were times he was scolded for parking in a handicapped spot. But weakness of Santa Lucia's respiratory muscles probably was already present when he started work as a children's therapist in the Tampa-St. Petersburg area shortly after graduation.

"My voice was getting weaker," he says, "which was problematic for me socially and professionally." Santa Lucia sought help from a speech therapist. (Respiratory muscle weakness can be insidious in myopathies. A weakening voice, weak cough, respiratory infections and daytime sleepiness or mental fogginess are some of the warning signs.)

But then, in January 2005, only a month after starting speech therapy, Santa Lucia began having abdominal pain that was severe enough to send him to the local emergency room and to supplant all other concerns. "I was diagnosed with an abscessed colon," he says. "I was treated with antibiotics in the hospital for a week, and the abscess cleared up." But doctors advised him to have elective surgery to remove the damaged part of his large intestine.

After postponing the surgery for a year and half, Santa Lucia finally decided to undergo the procedure.

All went well until it came time to remove the breathing tube in his throat that's normally used during surgery.

Ten days after the colon operation, when Santa Lucia was still unable to breathe without the tube connected to a ventilator, doctors performed a tracheostomy, surgically inserting a smaller tube into his trachea for long-term respiratory support.

After his family helped him transfer from the hospital in Florida to one closer to his New Jersey home, he remained on tracheostomy ventilation and was fed through a gastrostomy tube into his stomach for two months. "I remained too weak to stand up for the duration of my stay there," he says. "Their goal was to wean me from the ventilator and tracheostomy. However, they were unable to do so. Their plan at that point was to transfer me to a nursing home."

Miracle in Newark

Fortunately for Santa Lucia, his New Jersey home was, like the Foyes', not far from the MDA clinic at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, where John Bach has specialized for years in the treatment of respiratory muscle weakness.

Treatment of respiratory failure that results from lack of breathing muscle strength is fundamentally different from treating respiratory failure in lung disease, although physicians who don't specialize in neuromuscular disease often don't know this.

"My mother found Dr. Bach on the Internet and contacted his office," Santa Lucia recalls. "It was a half hour away, in Newark, and I went there by ambulance. After six months of struggling with breathing, I could breathe on my own after two days of Dr. Bach's methods. It was like a miracle."

Bach removed Santa Lucia from supplemental oxygen, which is rarely indicated in neuromuscular disease, and more than doubled the volume of air he was getting with each breath from the ventilator. "Once I got the extra volume, I was fine," Santa Lucia says. Bach removed his tracheostomy tube and changed the system to a noninvasive (mask) interface, which Santa Lucia uses only at night.

"It was scary when I was unable to breathe," he says. "I almost died because of respiratory failure. To be able to go from that to complete independence has changed my life completely."

Prediction of severity remains elusive

Prediction of severity remains elusive

The course of an autosomal CNM is generally hard to pin down, says Beggs, and even X-linked MTM can vary considerably from one person to another. "Even among genetically homogenous [similar] X-linked MTMs, the clinical presentation and prognosis is quite variable and unpredictable," he notes.

Beggs and his colleagues in Boston want to find out what makes CNMs tick, and welcome anyone with CNM and other genetic myopathies to participate in research. For information, call (617) 919-2169, or send e-mail to etaylor@enders.tch.harvard.edu.

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information