Sorting Out Speech Services

"People always think speech therapy is related to speech and not to assistive technology or swallowing disorders," says Sharon Veis, a speech-language pathologist at the Voice, Speech and Language Service and Swallowing Center of Northwestern University in Chicago.

Veis says she doesn't mind being called a "speech therapist," but she and other speech professionals prefer the term used by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, which is "speech-language pathologist," or simply SLP.

ASHA says SLPs are "professionals educated in the study of human communication, its development and its disorders. By evaluating the speech, language, cognitive-communication and swallowing skills of children and adults, the speech-language pathologist determines what communication or swallowing problems exist and the best way to treat them."

ASHA says SLPs are "professionals educated in the study of human communication, its development and its disorders. By evaluating the speech, language, cognitive-communication and swallowing skills of children and adults, the speech-language pathologist determines what communication or swallowing problems exist and the best way to treat them."

Or, as another SLP puts it, "We do more than just teach little kids to say 'r.'"

SLPs and neuromuscular disease

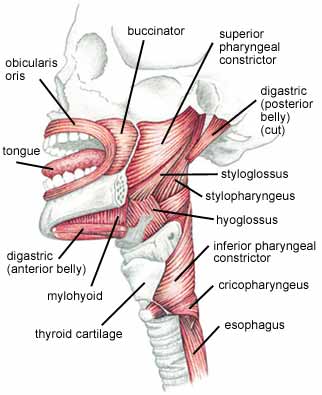

In many neuromuscular disorders, the muscles that control speech and swallowing weaken, either because the muscles themselves or the nerves that control them are affected. In the vast majority of people with these disorders, the brain and its language-processing centers are intact, and the problem is only one of moving the mouth and tongue or the throat muscles to form words and use the voice. In some disorders, respiratory function is compromised enough to adversely affect speaking ability.

Speech or swallowing are often affected in oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy, inclusion-body myositis, myotonic muscular dystrophy (especially the severe, congenital form), other congenital muscular dystrophies, nemaline myopathy, myotubular myopathy, Friedreich's ataxia, the myasthenias, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and spinal-bulbar muscular atrophy. In some children with early-onset muscular dystrophies or mitochondrial disorders, the brain may also be involved, complicating the speech problem.

When speech muscles are weak or when weak respiratory muscles interfere with the breath support needed for speech, exercises may not do any good, Veis says, but slowing the rate of speech can be learned with practice and can increase speech intelligibility.

"I ask them to say fewer words per breath, to enunciate syllables, pausing between phrases, maybe even pausing between words," she says. "There are pacing methods, where you tap on a table to pace yourself."

"I ask them to say fewer words per breath, to enunciate syllables, pausing between phrases, maybe even pausing between words," she says. "There are pacing methods, where you tap on a table to pace yourself."

Another technique favored by Veis and her colleagues at Northwestern is the alphabet board. "The person touches the first letter of the word that they're saying, which slows down speech and also helps the listener get an idea of the first sound in any word, which is often the most important thing."

Touching a letter eliminates misinterpretation of sounds. "There may be confusion, for example, between a 'd' and a 't' or between a 'k' and a 'g' sound," which the alphabet board can overcome, Veis says.

Veis is skeptical that much can be done, particularly in severe neuromuscular disorders like ALS, to improve the range of motion of the speech organs. "If the tongue only goes so far, it only goes so far," she says. If speech can't be made intelligible, with or without the help of simple devices, the next step, which is to get a high-tech device, can be taken.

Such devices, known these days as AAC, for augmentative and alternative communication, can substitute for speech. Veis says the philosophy at her clinic, and of today's SLPs in general, is that learning such "compensatory" techniques is just as important as learning techniques to help improve natural speech.

In severe and progressive disorders like ALS, Veis thinks some advance planning is essential. "It's important to anticipate some of the progression, so that if and when the need arises for an augmentative communication system, one has already explored with the client some of the basic information. They should know what kinds of devices are available — small versus large, portable versus nonportable, simple versus complex computer technology.

"It's better to have that discussion before you need to, to find out the patient's background with the use of devices, their comfort level, whether they have computer knowledge or not, their finances," Veis suggests. "Of course, some needs may change along the way. They may need to change devices if they can't use a typing system anymore. If you're talking about a progressive disease, needs change over time. In a more static disease, needs may also change but because of different issues."

|

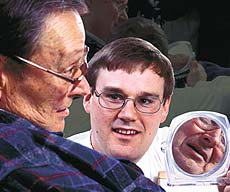

| Speech-language pathologist Jeff Edmiaston at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis shows Keith Vinyard, who has amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, how to tuck his chin during swallowing. |

|

| Edmiaston and Vinyard work on a DynaVox 3100, a computerized speaking device. |

|

| A mirror helps the speech therapy client see how exaggerated mouth movements can improve speech intelligibility. |

Safer swallowing

Cathy Lazarus is also an SLP at the center at Northwestern, but her specialty is swallowing disorders. Because the same muscles are involved in voicing as in swallowing, she also specializes in disorders involving sound production.

To diagnose the nature of a speech or swallowing problem, "we get most people down to X-ray," Lazarus says. They're given water mixed with liquid barium (which shows up on X-ray film), a barium paste and a quarter of a cookie covered with barium paste to examine how they swallow different substances.

"You can get information about the oral phase of a swallow just with the person sitting in front of you," Lazarus says, "but not about the pharyngeal [throat-related] phase." She and other SLPs are intimately involved in seeing that swallowing tests are done and properly read.

Early in the course of a disease, some techniques to improve the safety of swallowing can be put into place. "We can do some posture modification and also modify their diet," Lazarus says. But later on, "we may need to discuss the need for nonoral feeding. We do a lot of counseling."

SLPs, Lazarus says, "are the most well versed in the anatomy of the oral cavity, pharynx [throat] and larynx [voice box] and are the most well equipped to evaluate and treat swallowing problems."

Getting that language piece in

When children have neuromuscular disorders that interfere with their speaking, language development itself can be threatened, says Sydney Mason, an SLP who specializes in treating young children through Hope Children's Services in Rockledge, Fla.

"The big piece of who I am is that I get that child to communicate through language," Mason says, adding that there are a variety of ways to do that.

"In children with muscular dystrophy, we look at the musculature," Mason says. "If the speech musculature is not there, then we think about how we would go about getting the sound. Different sounds can be produced in lots of ways.

"For example, take the 's' sound. [Most people] produce a clear 's' with the tip of the tongue behind the teeth. But if a child can't do that, we can try to use the sides of the tongue, to get the sound approximately. A lot of times it's trial and error."

When respiratory support is insufficient for voicing, Mason looks at improving it. "You look at respiratory mechanisms, working with occupational and physical therapy to activate the rib cage muscles as much as possible," she says. Recalling a child who had a mitochondrial disorder and poor breath support, she says, "We did a lot of blowing activities, to get good respiratory support. Vocalization comes after that many times."

For Mason and her early-childhood team, even if a child can't learn to speak, communication and language development are still vital, and alternatives to speaking have to be found.

"In our practice," Mason says, "the emphasis is on birth to age 5. We may introduce an augmentative communication system, and then, after the child goes to school, they would fully implement this."

Another alternative system is sign language, if the child's hand muscles are working well enough for this. The child with the mitochondrial disorder learned the signs for "eat," "more" and "all done," while also learning other ways to communicate.

"The point is not necessarily for the children to be signers, but for them to have a visual complement to verbal language," Mason says. "It's absolutely important for the child to learn early that 'when I do something, something happens. When I make eye contact with my mommy, she does something.' Those are the earliest lessons that we try to get parents to understand."

Even if finger and hand function is later lost in a progressive disorder, the early boost to language makes learning some signs worthwhile, Mason believes.

The Hope center also uses picture systems and computerized devices, with the same underlying goals.

"Communication," Mason says, "is the one thing that is going to open up the child's world to him or her. You've got to figure out a way to help the child communicate and interact with others in his environment."

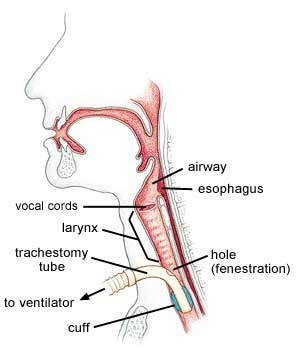

Special concerns with trachs and vents

It's a fairly common belief, perhaps aided by television dramas, that tracheostomies and ventilators put an end to normal speaking and swallowing. That's simply not so, says SLP Marta Kazandjian, who specializes in helping ventilator users at Silvercrest Extended Care Facility and the New York Hospital Medical Center of Queens, both in New York.

"The role of the speech pathologist, whether the patient is vent-dependent or not vent-dependent, is to be sure the patient can communicate during their waking hours," says Kazandjian. "If the patient is able to voice during periods of the day, you try to facilitate voice production. If you're unable to do that, you use alternative means of communication to make sure they can make their needs known."

Many tracheostomy tubes, Kazandjian explains, have an inflatable plastic cuff that keeps air that flows into the throat from the ventilator from flowing back up toward the larynx and vocal cords. Instead the air is directed downward into the lungs, where it's needed for breathing. When the cuff is fully inflated, with many types of tubes, no air can get to the vocal cords, and no sound can be made. An inflated cuff also interferes with swallowing reflexes.

Fortunately, Kazandjian says, most people with neuromuscular disorders don't need to have the cuff fully inflated all the time. "It's rare that patients with neuromuscular disease can't tolerate cuff deflation," she says. "Frequently, what we're able to do is at least get them to tolerate partial deflation. The goal is, despite the degenerative condition, to get the patient to tolerate full cuff deflation, so that we can then use other tools."

Fortunately, Kazandjian says, most people with neuromuscular disorders don't need to have the cuff fully inflated all the time. "It's rare that patients with neuromuscular disease can't tolerate cuff deflation," she says. "Frequently, what we're able to do is at least get them to tolerate partial deflation. The goal is, despite the degenerative condition, to get the patient to tolerate full cuff deflation, so that we can then use other tools."

The other tools include speaking valves, such as the popular Passy-Muir valve, which add to the vent user's speaking ability by stopping any air from flowing out through the tracheostomy tube while the person is trying to speak. A deflated trach cuff may allow some air to flow up to the vocal cords, Kazandjian explains, but enough air may still be leaving the throat through the open trach tube to keep one's voice from being effective unless the tube is plugged with a closed valve during speaking attempts.

Of course, other methods of communication, such as computers and alphabet boards, can also be used by people on ventilators who have limited speaking ability. But even the ability to say "yes" or "no" with one's own voice "can be very powerful," Kazandjian notes.

Ventilator settings can be adjusted to help a person get upper airway flow for speech and still maintain adequate pressures for respiratory function, Kazandjian says.

"Sometimes you have to get the ventilator to work for the patient as opposed to the patient working for the ventilator. It's a balancing act to ensure that the patient is being adequately ventilated, that they maintain normal carbon dioxide and oxygen levels, while at the same time being able to use upper airway flow. You can frequently make changes to the ventilator settings that assist the patient in tolerating cuff deflation, like giving them more volume or maybe more pressure support or changing the rate on the ventilator. There's no cookbook approach."

A similar balance can be struck when it comes to eating and drinking, Kazandjian believes. She warns against a misconception that an inflated trach cuff means food can't go down into the lungs. It usually slips down around the cuff, she notes, while at the same time the cuff interferes with the person's normal swallowing reactions that would direct the food down the esophagus.

A better solution, in Kazandjian's experience, is to allow some food to be taken by mouth, if that's important to the person, with safety measures in place to guard against inhaling food. "We try to give them at least a leak of the cuff, if not full cuff deflation, and do whatever we can to facilitate safer swallowing," she says. "There are a lot of techniques you can use to get secretions and food out if you do have a problem."

Getting help

So, how do you find an SLP, and how do you pay for the services and equipment?

"Getting reimbursement for adult care in speech pathology, for service or equipment, is difficult," says Jeff Edmiaston, an SLP at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis. But, says Edmiaston, it may be getting easier, at least for speech devices, because Medicare is changing the way it classifies these devices, which his clients so often need.

In the meantime, many private insurance plans will help with payment for at least some speech therapy or devices for adults, and many companies that make the devices have departments that assist clients with this funding. The DynaVox company, Edmiaston says, has about a 50 percent success rate in getting insurance to help with payment for its AAC devices.

For children, there are more options, because speech and language are integral parts of the federally mandated "free and appropriate public education" under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). As a result, speech therapy is relatively easy for children with disabilities to get through their school systems or through an early intervention program before they start school.

Speech services have their roots in schools and have long been tied to education, says Sydney Mason. That makes it somewhat easier to get services for children, but harder for adults, because medical insurance may not take speech services quite as seriously as it does other therapies.

Finding a Speech-Language Pathologist

- Your MDA clinic physician (MDA pays for one speech pathology consultation a year.)

- Your pediatrician

- Your school system, particularly the school's Committee on Special Education, or whoever generally puts together a child's IEP (Individualized Education Program)

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA)

ASHA Action Center

Rockville, Md.

(800) 638-8255

actioncenter@asha.org

www.asha.org; click on Public Information

ASHA can help you find an SLP in your area.

Communication Independence for the Neurologically Impaired (CINI)

(212) 385-8045

cini@cini.org

CINI is a nonprofit organization co-founded by Marta Kazandjian that specializes in helping those with ALS and related disorders to use augmentative and alternative communication devices.

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information