Scoliosis Surgery

Setting the record straight

"I've had a lot of different surgeries for a lot of different problems," says Todd Palkowski of Franklin, Wis. "Not all of them have been successful. But this one works."

He's talking about the spinal fusion he underwent almost 20 years ago to correct severe scoliosis. Palkowski, who has spinal muscular atrophy, was 13 at the time. Like many of those with SMA and nearly all of those with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, his spinal muscles had become too weak to hold him erect. The surgery, which involved the placement of a pair of metal rods down the length of his spine and the fusion of his vertebrae, has kept him upright and properly seated in his wheelchair. It gave Palkowski the mobility to work full-time as a recreation therapist.

Upright posture is normally maintained through the dynamic interaction of many different muscles. By pulling against each other and against the vertebrae, or backbones, they keep the spine from bending under the weight of the upper body. When viewed from the back, the vertebrae line up one on top of the other, allowing weight to be transferred downward to the pelvis. When the muscles responsible for holding the vertebrae in this position weaken, the vertebrae can be pulled out of alignment, a condition known as scoliosis.

Upright posture is normally maintained through the dynamic interaction of many different muscles. By pulling against each other and against the vertebrae, or backbones, they keep the spine from bending under the weight of the upper body. When viewed from the back, the vertebrae line up one on top of the other, allowing weight to be transferred downward to the pelvis. When the muscles responsible for holding the vertebrae in this position weaken, the vertebrae can be pulled out of alignment, a condition known as scoliosis.

This often results in the development of a C-shaped curve, as the balance system tries to compensate for the misalignment. A lean to the left at the top, for instance, shifts the center of gravity to the left. To prevent tipping over, the lower spine is shifted to the right in an attempt to keep the center of gravity over the pelvis.

While the normal spine is straight when viewed from the back, the side view shows a normal S-shaped curve. From the pelvis, the spine travels slightly forward, then curves back again as it meets the bottom of the rib cage. The upper portion of the spine curves gently forward to the shoulders. Excess curvature of this region is known as kyphosis, and this is common in several neuromuscular diseases. Above the rib cage, the neck vertebrae curve back again slightly, until they meet the skull at the top of the neck. Because each is due to muscle weakness, scoliosis and kyphosis often occur in combination.

In Duchenne, both are quite common. The onset is usually at about age 10. It accompanies the transition to the wheelchair, although one doesn't cause the other: Both are due to the underlying progressive loss of muscle strength. However, the increase in time spent seated may accelerate the progression of the curve, as a boy leans on the chair armrests. The rapid growth that occurs around this age also plays a part, as the increase in weight and height both put extra strain on weakened muscles.

Scoliosis in SMA is tied to age of onset, says Dr. Walter Greene, chairman of pediatrics at the University of Missouri School of Medicine in Columbia. "For patients whose SMA is diagnosed at age 5 or 6, and who keep walking for several years afterward, only about half develop scoliosis. In more severe case, where the person has never walked, scoliosis is almost certain."

Scoliosis and kyphosis affect about 15 percent of those with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, usually developing in the teens. In some, the curves remain mild, while for others, they progress rapidly and require surgical correction.

Scoliosis can also occur in Friedreich's ataxia, myotonic dystrophy (MMD), facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy and a number of congenital myopathies. In these diseases, too, the progression and severity are variable.

An array of benefits

While scoliosis is also found in the general population, its treatment in those with neuromuscular disease differs in some important ways, says Dr. Freeman Miller of the DuPont Institute in Wilmington, Del.

The goals of spinal fusion surgery for scoliosis (and kyphosis) are to ensure proper seating in the wheelchair, to prevent pain, to improve body image and to improve the effectiveness of minimally invasive respiratory aids.

The severe curvatures resulting from collapse of the spinal support system result in a weight imbalance even while seated. "When this happens, weight will be borne unevenly by the left and right buttocks, often resulting in pressure sores and even skin breakdown," says MDA clinic director Dr. John Bach of the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey in Newark.

The same thing can happen to the elbow and forearm if they are used to support the leaning upper body. "If the curve gets really bad," Bach notes, "the ribs push hard into the abdomen or against the hip bone, which can be very painful. As the vertebrae press against each other, the nerves can get pinched, leading to chronic pain. Ultimately, sitting becomes impossible."

Straightening the spine also improves appearance, and frees the arms of the need to support the upper body. "Also," Bach says, "with a straight spine you can use a pneumobelt to assist respiratory function when your breathing gets weaker." A pneumobelt is a device worn around the waist. As it inflates, it pushes against the abdomen, causing exhalation without effort. Inhalation then occurs more easily as the belt deflates.

"Most people much prefer it [to a nosepiece, mouthpiece or trach (tracheostomy)]," Bach says. "But you can't use it if you have uncorrected scoliosis."

Before spinal fusion became common in the late 1970s, many of those with neuromuscular disease-caused scoliosis were treated with braces that surrounded the chest and abdomen. In Duchenne, this approach did little good, because it didn't stop the spinal collapse that resulted from muscular weakness.

"The progressive weakening of the respiratory muscles makes surgery much more risky later in the disease," Bach says. "You should never brace the spine of a Duchenne patient to prevent scoliosis. You are just postponing the real treatment until you miss your opportunity."

Bracing works well in SMA, in which scoliosis often appears at a much younger age. "We try to slow down the scoliosis with bracing while the children grow," Greene says. "The timing depends on a number of factors: how much weakness there is, how flexible the spine remains, how fast the curve is progressing, and how well the person tolerates the brace. We'd like to wait at least until age 10 before we fuse the spine."

If surgery is done too early, the front of the spine will continue growing while the rear cannot, causing an arched back and difficulty maintaining forward vision. Todd Palkowski was in a brace from the time of his diagnosis at age 4 until his surgery at 13. "As much as I hated that brace, when the time came, I was afraid to take it off. I sure don't miss it, though."

The right time to operate

Scoliosis surgery can usually be planned in advance, but there are exceptions. Will Spence of Denver, who has Duchenne, was in a car accident at 15.

"I was doing pretty well before then, but I broke an arm and a leg, and had to spend a long time in bed recovering." Already using a wheelchair, Spence noticed a rapid progression of his curvature. "It kind of took us by surprise," he says. Nonetheless, Spence had several months to think about the operation and to schedule around it.

To determine the appropriate time for the surgery, doctors pay close attention to two measurements. The first is the curve itself. Normally, the tops of the vertebrae are parallel with each other and with the floor, and lines drawn along the tops of separate vertebrae would never meet. When the spine is bent, such lines would meet, to form an angle. To assess the degree of curvature, an X-ray of the spine is taken, and lines are drawn along the vertebrae at the bottom and top of the curve. The angle formed is measured using a compass.

To determine the appropriate time for the surgery, doctors pay close attention to two measurements. The first is the curve itself. Normally, the tops of the vertebrae are parallel with each other and with the floor, and lines drawn along the tops of separate vertebrae would never meet. When the spine is bent, such lines would meet, to form an angle. To assess the degree of curvature, an X-ray of the spine is taken, and lines are drawn along the vertebrae at the bottom and top of the curve. The angle formed is measured using a compass.

"For scoliosis that isn't due to neuromuscular disease, an angle of 40 degrees is the usual indication for surgery," Bach says. "But for most of those with Duchenne, this curvature is reached after the respiratory muscles are too weak for safe surgery." Instead, a 25-degree curve is the cutoff point.

"If the curve gets to the point of 25 degrees, we can be pretty sure it's going to progress," Greene says.

However, scoliosis doesn't progress in all of those with a 25- degree curvature, Bach notes, and so the second measurement comes into play.

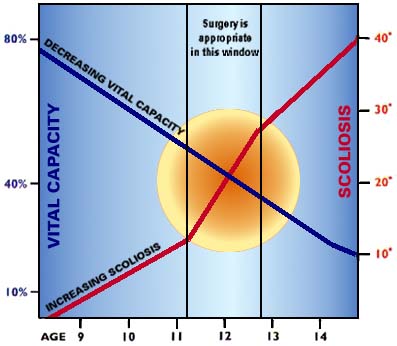

"Vital capacity" is the term used to describe the volume of air inhaled and exhaled with each breath. As a person grows, vital capacity increases. However, in Duchenne, the weakening of the respiratory muscles reverses this trend, and a plateau of vital capacity is seen in late childhood or early adolescence. Bach explains the significance of this plateau in making decisions about scoliosis surgery.

"If the plateau is very high, over 2,500cc [cubic centimeters], the rate of decline in vital capacity is very slow, so we can wait longer before deciding on surgery. Also, about 25 percent of those with high plateaus don't progress in their scoliosis. However, if the plateau is low, around 1,700cc, not only is it low to begin with, but the rate of loss is higher, and scoliosis appears in almost 100 percent of the children. If you wait in these cases for a 40-degree curve, the vital capacity will be too low to do surgery safely."

Doctors also measure the percentage of expected vital capacity, based on height, sex and age. In Duchenne, the vital capacity has usually dropped to 50 percent of expected by age 11, and continues to drop every year thereafter. Surgeons agree that, below 20 percent, surgery may be too risky. Many surgeons prefer to operate when vital capacity reaches 35 percent to 40 percent. At this point, it's usually late enough in the development of the curve to determine if the scoliosis will progress, but still early enough in the respiratory decline to permit safe surgery.

Improved procedures

Will Spence made his decision after talking with the surgeon, and with a friend who had experienced the same procedure. "He had excellent results, and that made a difference to me."

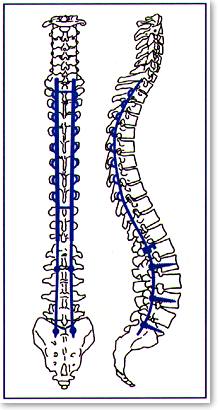

Procedures have changed significantly since the Harrington system was designed in 1962. It involved placing two metal rods side-by- side at the rear of the spine, and attaching them with hooks at the top and bottom. Surgery was followed by immobilization in a plaster body cast for many months, to allow the vertebrae to fuse together.

Procedures have changed significantly since the Harrington system was designed in 1962. It involved placing two metal rods side-by- side at the rear of the spine, and attaching them with hooks at the top and bottom. Surgery was followed by immobilization in a plaster body cast for many months, to allow the vertebrae to fuse together.

In the late 1970s, Dr. Eduardo Luque, an orthopedic surgeon in Mexico specializing in neuromuscular diseases, developed the segmental stabilization system. In Luque's system, the rods were wired to each of the vertebrae. They were bent to more accurately model the proper curvature of the back, and the vertebrae were treated to promote faster fusion. The Luque method allowed rapid post-operative mobility and a very high degree of correction.

Luque's method has been modified over the years. One popular system employs the "unit rod." Shaped like a hairpin, it travels up one side of the spine, turns at the top of the ribcage, then travels down the other side. Both ends are implanted into the pelvis. Other systems stop short of the pelvis.

Miller believes fusing to the pelvis gives better seating in almost every case. Greene thinks it may cause more seating problems than it cures, at least in Duchenne.

"Any time you fuse all the way to the pelvis, you are rock solid in one position; you have no give. If you are still a little out of balance after the surgery, it can be more difficult to sit comfortably." However, without fusion to the pelvis, Greene notes, there is more tilting of the pelvis over time.

Because of their relatively longer life expectancy, pelvic fusion is almost always done for those with SMA after they lose the ability to walk.

In other respects, most spinal fusion operations are quite similar to one another. The operation usually takes from three to four hours, and is done under general anesthesia.

An understanding of the concerns of anesthesia for those with Duchenne has greatly lessened the risk of a condition known as malignant hyperthermia, in which the body temperature rises suddenly. Certain types of anesthetics can bring on this condition, which can be life-threatening. However, avoiding these anesthetics and carefully monitoring body temperature during surgery have all but removed this as a problem.

Fusion is the goal

During the operation, two separate processes occur. The first involves placement and wiring of the rods. The wires are passed from the rod into the joint between two vertebrae. They then are threaded into the rear of the spinal canal, the hollow tube through which the spinal cord passes. They travel next to the spinal cord, then re-emerge from the spinal canal at the next vertebral joint. The proximity of the wires to the spinal cord introduces an additional risk.

"Fortunately," Greene notes, "there is a layer of fat which acts as a protective layer between the spinal cord and our wires. I've never actually heard of the wires causing problems."

The second procedure treats the vertebrae to promote bone fusion. The protective coverings on the adjoining surfaces of the vertebrae are removed. Natural healing of this region usually leads to fusion of the two vertebrae.

To increase the likelihood of fusion, small pieces of bone are usually grafted into place at these joints, to act as bridges between the vertebrae. In the early days of spinal fusion surgery, these pieces were removed from the patient's hip. Today, small fragments removed from the vertebrae themselves are used, or rice grain-size bone chips from the hospital bone bank are employed. Cleansed of blood and irradiated to destroy all the cells inside, they present no transplant difficulties.

The major surgical complication is blood loss. During the operation, between 3 and 6 liters are lost, and must be replaced by transfusion. Transfusions of this volume do lead to some post- operative complications, including pain and accumulation of fluid in the tissues near the surgical site.

Prednisone, one of only two medications shown to improve muscle strength in Duchenne, has the unfortunate side effect of thinning the mineral structure of bone. Miller says that "while prednisone certainly doesn't help the bone structure, my sense is that it doesn't make a big difference in how the surgery goes." He's concerned that long-term steroid use may lead to exceedingly soft bone.

Adjusting to changes

After the operation, most patients are kept on a respirator for 24 to 48 hours. This accomplishes several related functions. Since the muscles at the rear of the chest are necessarily damaged during the operation, their use immediately afterward causes pain. The respirator allows these muscles to rest. It also allows the use of morphine-based pain relievers, the side effects of which include depression of respiratory function. Finally, it promotes full ventilation, which reduces the risk of pneumonia, a serious post-operative threat.

In some cases, postural drainage of the lungs must be performed, since the combination of decreased respiration and increased fluid accumulation poses a danger to the lungs. This is done on a tilting bed, with the head lower than the feet, to allow fluid to drain out under the pull of gravity, sometimes aided by thumping of the back.

Most patients are back in their wheelchairs two days after the operation, and stay in the hospital for another week.

"We want our patients to begin working on breathing deeply at this point," Miller says. Because of the rigidity in the chest, it may be more difficult to breathe fully.

Spence found just the opposite. "My breathing was definitely better after the operation. That was one of the biggest changes." Nonetheless, while better posture can improve the mechanics of breathing, some vital capacity may be lost through the operation.

The shift in posture, of course, is one of the biggest changes. Says Palkowski, "I grew a foot during the operation, just from being straightened out." A wheelchair adjustment is necessary at this point, to accommodate these changes.

The increased stiffness, especially with fusion to the pelvis, can make for some initial discomfort. Spence found he needed a molded seat to get comfortable, a change he wasn't expecting. Greene notes that long-term discomfort is rare, and many who have had the operation find relief from long-term back pain.

Increased height can mean changes in feeding, since bending over to be close to the plate is not an option. Transfer techniques change as well.

"Since I can't curl up anymore, it's harder for me to be lifted by one person," Spence says.

Taller seating also uses up headroom in the car or van. And while the neck vertebrae remain unfused, allowing normal rotation of the head, there is a significant change in the mechanics of moving the upper body as a whole, since rotation of the spine is no longer possible. Turning around involves rotating the entire upper body, and the pelvis, too, if it's fused.

Planning for these changes before surgery, in consultation with occupational and physical therapists, can allow successful management of these problems.

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information