Managing Myasthenia

Array of treatments means myasthenia gravis usually isn't so grave

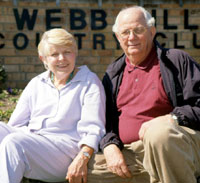

Charles Ranly is a busy man, but he always takes time to stop and smell the roses or more accurately, the pansies, zinnias, begonias and other seasonal flowers at Webb Hill, the 223-acre country club he owns in Wolf City, Texas.

Charles Ranly is a busy man, but he always takes time to stop and smell the roses or more accurately, the pansies, zinnias, begonias and other seasonal flowers at Webb Hill, the 223-acre country club he owns in Wolf City, Texas.

The club boasts an 18-hole golf course and has over 600 members. Ranly, 68, oversees 12 to 20 employees (depending on the season), hosts golf tournaments and civic events year-round, and personally attends to the 10,000 or so flowers that decorate the grounds.

But all of that seemed in jeopardy eight years ago, when Ranly experienced a series of unusual medical problems — first double vision, then difficulty chewing, swallowing and talking. A visit to Gil Wolfe, co-director of the MDA clinic at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, revealed that he had myasthenia gravis (MG) a disease that causes weakness and fatigue, sometimes affecting the muscles that control breathing.

At first, Ranly recalls, "I got depressed. I'm a real strong person and I couldn't believe this was happening to me." He worried that he might have to give up the country club. But thanks to medication and periodic rest breaks, he's kept his MG in check.

Wolfe is impressed, but not surprised, by Ranly's perseverance. "Taking care of MG patients is one of the more rewarding things that I do, because we can really help people," he says. "It's a very treatable disease."

But that doesn't mean that MG is simple to treat, he admits. There are many treatments available to people with the disease and finding the right ones for each patient can be a challenge.

The nerve-muscle connection

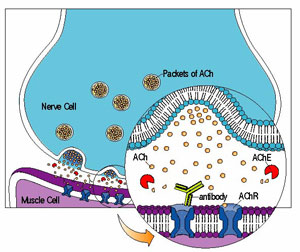

MG is an autoimmune disease, meaning that the immune system turns against the body's own tissues. In the case of MG, the immune system targets the connection between nerve and muscle, or the neuromuscular junction.

The normal sequence of events between nerve impulse and muscle contraction takes about a thousandth of a second. Nerve cells release a chemical called acetylcholine (ACh), which attaches to a docking site on muscle cells, called the ACh receptor. Once it's captured ACh, the receptor actually a pore in the muscle cell twists open, causing an inward flux of electrical current that triggers muscle contraction. These events are terminated (at least in part) by acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme that breaks down ACh in the space between the nerve ending and the muscle cell surface.

In most cases of MG, the immune system makes antibodies that recognize the ACh receptor. The antibodies, Y-shaped missiles that normally attack bacteria and viruses, destroy many of the ACh receptors on muscle. Consequently, the muscles response to repeated nerve stimulation declines with time, causing weakness and fatigue.

In most cases of MG, the immune system makes antibodies that recognize the ACh receptor. The antibodies, Y-shaped missiles that normally attack bacteria and viruses, destroy many of the ACh receptors on muscle. Consequently, the muscles response to repeated nerve stimulation declines with time, causing weakness and fatigue.

Of course, none of this was known in the late 19th century, when MG was first described in detail. Understandably, the outlook for patients was grim; in fact, the name of the disease, which literally means "grave muscular weakness," was chosen to emphasize its severe, often fatal course. Even in the early 20th century, many people with MG lost strength rapidly within a year or two of diagnosis, and they ultimately died of respiratory failure.

In the 1930s, the role of ACh at the neuromuscular junction was discovered, and soon, cholinesterase inhibitors drugs that block the breakdown of ACh by acetylcholinesterase became a standard treatment for MG. In the 1960s, researchers discovered the autoimmune nature of MG, and began attacking the disease at its roots using immunosuppressant drugs.

Today, thanks to these treatments and others, it's estimated that the mortality rate of MG is less than 5 percent.

Is it really MG?

Experts say the first step toward getting effective treatment for MG is an accurate diagnosis.

Double vision and droopy eyelids might lead a physician to suspect MG. Weakness of the extraocular muscles, those that control movement of the eyes and eyelids, is conspicuously absent in many neuromuscular diseases, but it's a common and early symptom of MG.

For about 15 percent of people with MG, the disease remains exclusively "ocular" for its entire course, but for most people, it eventually becomes "generalized," involving voluntary muscles throughout the body. If left untreated, weakness often spreads from the extraocular muscles to the rest of the face (including the jaw, throat, and tongue), then to the limbs and trunk, and finally to the respiratory muscles.

Weakness that fluctuates during the day and over longer periods, from months to years, is another hallmark of MG. But other diseases can cause similar symptoms, and to the untrained eye, some of these can look a lot like MG.

The most reliable indicator of MG is a blood test that reveals antibodies to the ACh receptor, says Daniel Drachman, director of the MDA clinic at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

But that test isn't foolproof, Drachman points out. "We've known for a long time that people with mild MG may have no ACh receptor antibodies, and that as many as 15 percent with generalized MG don't have the antibodies," Drachman admits.

A 2001 study showed that many of these seronegative MG patients have antibodies to MuSK, a protein that helps organize ACh receptors on the muscle cell surface. Unfortunately, blood tests for detecting the MuSK antibodies aren't yet commercially available.

If the blood test for ACh receptor antibodies is negative, the next step is usually electromyography (EMG), which involves using electrodes to measure a muscles response to nerve impulses. Edrophonium (Tensilon), a fast-acting cholinesterase inhibitor, might be given as a test to temporarily improve neuromuscular transmission.

Finally, "It's key to distinguish MG from congenital myasthenic syndromes," Drachman says. These diseases, related to but different from MG, are caused by genetic defects in the ACh receptor and other components of the neuromuscular junction, and thus can share symptoms with MG. Some even respond well to cholinesterase inhibitors, but they aren't treatable with immunosuppressant drugs.

A family history of myasthenic symptoms, childhood onset and a seronegative blood test for MG generally favor a diagnosis of CMS.

The path to treatment

Once a diagnosis of MG is established, both doctor and patient face many decisions regarding treatment. Most of the available medications and procedures have side effects, from mood changes to gastrointestinal problems, and a few have been linked to more serious ailments, including osteoporosis and kidney damage.

The balance between risk and benefit must be weighed separately for each patient, Wolfe says.

"There's really not a blanket approach to treating MG," he explains. "You have to individualize therapy by factoring in a variety of issues, including the severity of the disease and other conditions present in the medical history."

In addition, he says, "you have to factor in the patient's perspective on their disease on how well they're functioning now and what things they'd like to be able to do better." For example, someone who has a physically demanding career might prefer an aggressive, risky treatment over a less risky, slower-acting treatment; someone who's retired might prefer the opposite.

Donald Sanders, director of the MDA clinic at Duke University in Durham, N.C., says that, all things considered, cholinesterase inhibitors are usually the first-line treatment for MG. These drugs, which include pyridostigmine (Mestinon) and neostigmine (Prostigmin), can alleviate symptoms within minutes, and have no major side effects, he points out.

"Occasionally, they produce enough improvement that other treatments aren't necessary, particularly in patients with mild disease. But that is the exception rather than the rule," he says.

While cholinesterase inhibitors boost the amount of ACh that reaches muscle, they don't counter the immune system's assault on the ACh receptor. Thus, long-term treatment of MG usually requires immunosuppression.

Immunosuppressant drugs

Drachman, who's been practicing medicine for more than 40 years, remembers what the prognosis of MG was like before scientists understood its autoimmune nature.

In the 1950s, he says, "It was really bad. Many of these people were on respirators, they had feeding tubes. They were severely impaired or they'd die." He remembers one patient who was kept alive with an iron lung.

"The development of a variety of effective immunosuppressant drugs and the knowledge of how to use them both individually and in combination has been crucial to treating MG," he says.

Among these drugs, corticosteroid hormones and azathioprine (Imuran) are the most widely used.

Corticosteroids (which include prednisone) are relatively inexpensive and tend to act fast, producing improvement within weeks. But when taken over the long term, they can have many side effects, including weight gain, high blood pressure, cataracts, osteoporosis, and a blunting of mood and memory.

"The side effects of corticosteroids are a major limiting factor, but they can be dealt with in most patients," says Sanders, noting for example, that osteoporosis can be prevented with bisphosphonate drugs. Also, he says, corticosteroids can be used to induce rapid improvement, and then gradually tapered off and supplemented with other immunosuppressants.

"The main advantage [of Imuran] is that, except for uncommon side effects, it doesn't produce any long-term problems," he says. "The biggest limitation is that it takes a long time to work [three to six months]."

Both Sanders and Drachman have been investigating the possibility of treating MG with mycophenylate mofetil (CellCept), a drug originally developed to prevent rejection of transplanted organs. In pilot studies, about two-thirds of MG patients gained strength or were able to reduce their need for prednisone after taking CellCept for several months. Sanders is now heading a multicenter, three-year trial comparing CellCept plus prednisone to prednisone alone in MG.

Other options

Besides this arsenal of drugs, surgeries and other procedures are often successful in treating MG.

Thymectomy, the removal of an immune system gland called the thymus, is the oldest, first tried in 1913. From fetal development through childhood, the thymus produces immune cells called T-cells, but at puberty the gland starts to degenerate. About 15 percent of people with MG have a thymic tumor, called a thymoma, and another 65 percent have abnormal thymic tissue; theres evidence that these abnormalities might trigger the production of antibodies to the ACh receptor.

Thymectomy is necessary for treating thymoma, and often recommended for generalized MG.

"Evidence that it works [for MG] is more historical rather than scientific," Sanders says. "It's felt to be the only therapy capable of inducing a long-term drug-free remission, but there has never been a controlled study of it."

Wolfe plans to change that. He and colleagues are setting up a trial of MG patients (without thymoma) in which half will receive thymectomy and corticosteroids, while the other half will receive corticosteroids alone. The study's main goal is to determine what effect thymectomy has on corticosteroid requirements over the next few years.

Two other procedures bring about fast, but short-lived relief from MG, and thus are used mostly for myasthenic crisis, a rapid worsening of symptoms that can culminate in respiratory distress. (See "Myasthenic Crisis" below.)

Plasmapheresis, also called plasma exchange, was developed by MDA-funded researchers in the 1970s. It involves the use of an intravenous line to filter the blood and remove ACh receptor antibodies.

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy is essentially an injection of nonspecific antibody (immunoglobulin). Recent studies suggest that it works by dialing down the immune systems production of its own antibodies, much like the negative feedback circuit that tells the thermostat to stop pumping out heat once your house is warm.

The big picture

None of these treatments is a cure for MG, but all of them used alone or in combination can serve as powerful tools for managing the disease.

"A diagnosis of MG probably means life-long treatment for most people," Drachman says. "It entails a big commitment on the part of the doctor and the patient to take care of it, follow it and not let it go."

In very rare cases, MG is "refractory" or resistant to treatment (see "Refractory MG," below). But for most people, the disease isn't nearly as grave as the name implies.

Just ask Charles Ranly.

Just ask Charles Ranly.

Since his diagnosis, Ranly has taken Mestinon, Imuran and prednisone. He's seen his energy go down and his weight go up. He's had two myasthenic crises and two corresponding sessions of plasmapheresis.

He used to work at his country club seven days a week, six to eight hours a day; MG has forced him to cut his schedule in half. He used to play golf at a professional level, and MG has put an end to his game altogether. But it hasn't stopped him from enjoying life.

"Now I get my enjoyment from visiting with my [country club] members and planting flower beds," he says. "The only thing I have to do is take my medication, slow down and rest properly.

"Having a facility like this and making it work, I'm living the American dream."

Myasthenic crisis: be alert, not afraid

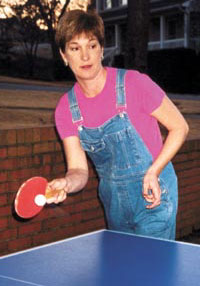

Judy Walsh will be the first person to tell you that MG can be unpredictable, with a potential for myasthenic crisis a rapid worsening of symptoms that can lead to respiratory failure.

She'll also tell you that she doesn't let that unpredictability dominate her life.

Walsh, 46, lives in Tiverton, R.I., and is a pediatric psychotherapist. About nine years ago, she noticed that the muscles in her neck felt weak, and eventually, she started having problems with swallowing and speech. At work, it became difficult for her to talk with patients.

In 1996, after a referral to the MDA clinic at Rhode Island Hospital in Providence, she was found to have MG. She was treated with a thymectomy and put on Mestinon and prednisone.

In 1996, after a referral to the MDA clinic at Rhode Island Hospital in Providence, she was found to have MG. She was treated with a thymectomy and put on Mestinon and prednisone.

"Within a year," she says, "I was pretty stable and back at work full time. I would have periods of exacerbation and I'd go in for plasmapheresis or IVIG, but I went on pretty well for a while."

When she had one of those exacerbations in spring 1999, she set up an appointment for IVIG a week later.

Although she didn't know it at the time, she was on a downward spiral toward a severe myasthenic crisis. Often, it's possible to identify a specific trigger for myasthenic crisis, such as a respiratory infection, a traumatic injury or stress, but Walsh doesn't remember one.

"When I got to the hospital, I put on my pajamas and got into bed. And in a matter of hours, I couldn't move my arms or legs," she says. "I thought I was dying."

Indeed, she came close. She stopped breathing, and was put on a respirator and a feeding tube for four weeks, while doctors pumped her with prednisone and Imuran. She lost 30 pounds, and had to stay in the hospital's intensive care unit for a month.

When she left the hospital, her swallowing problems persisted, so she continued to rely on the feeding tube for several months. She returned to the hospital for plasmapheresis once a week.

With continued plasmapheresis (now, she gets it about once every three months), and a familiar litany of drugs (Mestinon, prednisone and Imuran), Walsh's MG has stabilized again. She's back at her office three days a week and "has an active life," she says.

She doesn't dwell on the possibility of another myasthenic crisis, but she's prepared for it. She's become educated about MG, maintains a good rapport with her doctors, and knows to seek medical attention at the first signs of increased weakness.

"[Myasthenic crisis] can be frightening," she says. "But once you realize you can get better, you get back into gear and take charge of your life again."

Refractory MG meets its match?

A few years ago, if someone had tried to tell Lynn Castro that MG was a treatable disease, she might have responded by saying something unladylike.

After a car accident in 1998, Castro gradually recovered from her injuries, but began having episodes of labored breathing. A visit to the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital, near her home in Vestavia Hills, Ala., revealed that she had MG.

Immediately after the diagnosis, she started taking Mestinon and getting regular sessions of plasmapheresis. (She was already taking prednisone for lupus erythematosus, an autoimmune disease frequently associated with MG.)

Immediately after the diagnosis, she started taking Mestinon and getting regular sessions of plasmapheresis. (She was already taking prednisone for lupus erythematosus, an autoimmune disease frequently associated with MG.)

Despite those measures, she continued to have problems. At home, she used a BiPAP (a type of ventilator) to support her breathing while she slept. She couldn't climb the stairs, and during meals, she sometimes stopped eating because she didn't have the energy to continue.

In 1999, she was hospitalized several times for myasthenic crises. She was given a thymectomy and IVIG, but to no avail.

"I still kept having crises," Castro, 38, recalls. "I was going in and out of the hospital every other month, getting intubated each time." She was told that, one day, she wasn't going to make it to the hospital on time.

Then, in early 2000, her doctors learned that Daniel Drachman, director of the MDA clinic at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, was testing a new treatment for refractory MG MG that doesnt respond to conventional treatments.

Drachman's treatment involved a high-dose, intravenous infusion of cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), a drug traditionally used to treat cancers of the immune system. The procedure, given over four days, is believed to destroy mature immune cells but spare their progenitors in bone marrow. Drachman hoped that it might be used to "reboot" the immune systems of people with refractory MG.

"We knew it was a drastic approach, but since nothing else was working, my husband and I felt like we didn't have any alternative," Castro says.

So, in March 2000, she traveled to Baltimore, where she spent five days getting the treatment at Hopkins and another five weeks in a rented apartment, being monitored daily at Johns Hopkins, with frequent visits from her family.

Fast-forward to the present, and she seems to be in complete remission. "I can do so much now that I couldn't do before," she says. "I can go on walks, use exercise machines; I've even started playing basketball with my daughter again." She had one crisis soon after the treatment, but hasn't had any since.

Three other people with refractory MG have experienced equally spectacular results.

Is it a cure?

"It's too early to tell," Drachman says. "The patients treated with the procedure are doing well, but they still have [ACh receptor] antibodies" a sign that the underlying disease is still there. In any case, he emphasizes, since the treatment carries risks of infection and hemorrhage, its use will probably stay limited to refractory MG.

"For me," Castro says, "it has been [a cure]. According to the antibody levels, I still have the disease but I don't have any symptoms. It's not even a part of my life anymore."

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information