Cardiac Care in MMD: Lack of Symptoms May Mask Deadly Problems

When scarring develops in the heart's conduction system, abnormal heart rhythms can develop, sometimes without the person recognizing that anything is wrong

In 2006, Ron Hayes was a 54-year-old executive at Procter & Gamble in Cincinnati when he began noticing some weakness in his hands. "I was trying to clean my glasses," he remembers, "and my thumb couldn’t push the spray." A visit to a hand surgeon resulted in a referral to a neurologist and ultimately to a diagnosis of adult-onset MMD1. A DNA test of Hayes’ blood cells revealed 131 CTG repeats, consistent with the mild end of the MMD1 spectrum. In fact, Hayes had been active in sports in high school and had a football scholarship in college.

A DNA test of Hayes’ blood cells revealed 131 CTG repeats, consistent with the mild end of the MMD1 spectrum. In fact, Hayes had been active in sports in high school and had a football scholarship in college.

A DNA test of Hayes’ blood cells revealed 131 CTG repeats, consistent with the mild end of the MMD1 spectrum. In fact, Hayes had been active in sports in high school and had a football scholarship in college.

His son, Doug, had been diagnosed with MMD1 in 2001, at the age of 22, but with very different disease manifestations from his father’s. (See Juvenile-Onset MMD1 Can Cause Cognitive, Behavior Challenges.) Meanwhile, before the hand weakness, the only significant event in Hayes’ health history had been cataract removal in his mid-40s.

Hayes’ diagnosis came fairly quickly, probably because of the family’s awareness of the disease. Many people with MMD, even today, go through what’s referred to as a "diagnostic odyssey," as they visit doctor after doctor for seemingly unrelated symptoms.

In 2008, after he had retired and moved to Denver, Hayes’ MDA clinic physician sent him to a cardiologist, who fitted him with a Holter monitor, a device that continuously records an electrocardiogram (EKG) for at least 24 hours while the wearer goes about his normal daily routine.

The Holter monitor revealed that electrical signals were moving through Hayes’ heart more slowly than normal, a problem known as a conduction disturbance. The immediate insertion of a pacemaker was recommended, and Hayes didn’t argue. His brother, suspected of having MMD but without a diagnosis, had died suddenly, probably of cardiac causes.

Today, Hayes plays golf and enjoys time spent with his children and grandchildren. He still has hand weakness and some weakness in his lower legs and takes medication to counteract afternoon sleepiness.

MMD, he says, "is not the end of your life" — but he realizes it might have been had he not sought cardiac care.

His advice: "Look at what you can still do, and don’t assume you can’t do things — but see a cardiologist."

Scarring impairs conduction of electrical impulses

Scarring impairs conduction of electrical impulses

William Groh is a cardiac electrophysiologist at the University of Indiana’s Krannert Institute of Cardiology. Groh has a special interest in the cardiac complications of MMD1 and receives MDA support to study them.

Although his formal research has focused on MMD1, Groh also sees people with MMD2 in his practice.

"My experience is that the severity of heart involvement is significantly less in MMD2," he says. "But if they develop issues, it seems to be along the same lines. I don’t think that there have ever been real good studies [of the cardiac aspects] in MMD2. Case reports of individual patients with problems aren’t going to tell you what’s going on in terms of the whole population."

By contrast, for more than a decade, Groh and his colleagues have studied more than 400 MMD1 patients drawn from some 20 MDA clinics. Unlike most studies by cardiologists, Groh’s study didn’t confine itself to patients who were referred for cardiac evaluations because they had developed signs or symptoms.

"We took all comers," he says. "We followed all of those patients, and we were able to determine cardiac risk factors."

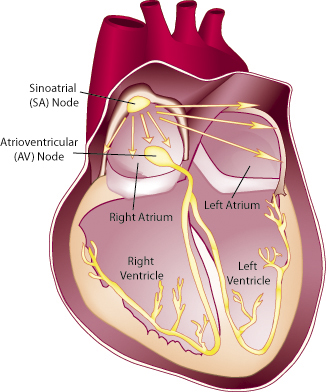

Cardiac disease in MMD1, Groh says, is nearly always conduction disturbance, resulting from the gradual replacement of the heart’s conductive tissue with scar tissue, a process known as cardiac fibrosis.

"It’s the conduction [of electrical signals that move through the heart] that appears to be first disturbed in patients with myotonic dystrophy," Groh says.

Conduction disturbance can lead to abnormal heart rhythms called arrhythmias. Arrhythmias that are too slow sometimes require a pacemaker that delivers regularly timed electrical impulses to bring the heart rate up to normal.

When the heart rhythm is too fast, an implantable defibrillator can deliver an electrical shock to restore a normal heart rhythm. (These are sometimes called implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, or ICDs.)

Although fibrosis seems to particularly affect the heart conduction system, the entire heart muscle can be affected as well, says Groh. However, he notes, only rarely do people with MMD1 develop abnormalities in the heart tissue responsible for the pumping of blood, a condition known as cardiomyopathy.

Actual heart failure (partial or complete failure of the pumping mechanism) is uncommon in people with MMD, Groh says. "If they do develop it, it tells us that the heart is really significantly affected. We see that in only a small percent of our population."

Rather, Groh summarizes, "We think the underlying problem is fibrosis and abnormalities in the heart that seem to specifically and primarily affect the conduction system, the specialized tissue that allows for electricity to flow through the heart. It leads to a higher risk of arrhythmias, and a small percentage of patients develop cardiomyopathy."

The most serious arrhythmias are those that cause the lower chambers of the heart — the ventricles — to stop beating or to beat too slowly to sustain life; or to beat in a fast, uncoordinated and ineffective way.

Both these fast and slow ventricular arrhythmias can lead to sudden death, and people with MMD1 unfortunately are at increased risk for that.

Atrial fibrillation may go undetected

About 10 percent of people with MMD1 in Groh’s study developed atrial fibrillation, a rapid, uncoordinated contraction of only the heart’s upper chambers (the atria,) which normally route blood from the circulation to the ventricles, which then pump it around the body.

It’s a serious problem, because the turbulent blood flow it causes can lead to clots and strokes. Although generally not considered as serious as a ventricular arrhythmia, Groh believes it’s an indicator that fibrosis, which is progressive, is under way in the heart.

"Patients with myotonic dystrophy are getting atrial fibrillation in their 40s and 50s at a rate of about 10 percent," he says, while in people without MMD, "we see that frequency in people in their 70s and 80s. So it’s an early degeneration of the heart."

Early, yes, but associated with increasing age. Children born with congenital-onset MMD1 typically don’t develop heart problems while they’re young, Groh says. "If they develop them, they don’t start until their 30s."

EKGs predict risk

Groh’s research has shown that a good screening test for atrial fibrillation and other arrhythmias is the EKG. "It’s a simple test, it’s a cheap test, and it can be done by your general doctor or a cardiologist," Groh says. "It’s a helpful test to predict who’s going to develop heart problems."

Groh’s research has shown that a good screening test for atrial fibrillation and other arrhythmias is the EKG. "It’s a simple test, it’s a cheap test, and it can be done by your general doctor or a cardiologist," Groh says. "It’s a helpful test to predict who’s going to develop heart problems."

He recommends that everyone with MMD1 get an EKG at diagnosis, to establish a baseline to which future EKGs can be compared. He prefers to have a new patient undergo 24-hour EKG monitoring as well as a simple "snapshot" EKG, and also to have an echocardiogram, an imaging study that reveals the structure of the heart.

A normal screening EKG, 24-hour EKG and echocardiogram are very reassuring, Groh notes. The usual recommendation is to repeat the EKG every year, and more often if symptoms appear. But Groh says some patients with normal EKGs may need a new one only every two or three years.

Groh recommends similar screening for MMD2 patients. However, he says, "The likelihood that the results will show no evidence of cardiac disease will be higher in MMD2 than in MMD1, and then screening can be done every two years or so, depending on the EKG and symptoms."

Symptoms important, but potentially confusing

Watch out for "palpitations" (the feeling that the heart is beating hard, fast and irregularly), severe lightheadedness, fainting, or significant shortness of breath, Groh says.

But, he cautions, symptoms can be confusing in people with MMD. "Patients with advanced myotonic dystrophy have respiratory issues," he notes, "so some of those symptoms, such as shortness of breath, might not necessarily reflect cardiac problems."

Another source of confusion, Groh notes, is that atrial fibrillation, dangerous in itself and a marker of progressive cardiac fibrosis, may not give rise to any symptoms at all in people with MMD1.

In people without MMD, a very rapid or irregular heart rate in the atria is conducted to the ventricles. The heart rate in the ventricles, normally 60 to 100 beats per minute, is increased to about 150 beats a minute, which generally causes feelings of discomfort, such as palpitations, that prompt medical attention.

But, Groh says, "Because atrial fibrillation tends to coexist in myotonic dystrophy patients with conduction disease, it’s often not conducted to the ventricles. So people may have a resting [ventricular] heart rate in the 70 to 80 beats per minute range and may have no symptoms at all. That can be dangerous, because there’s a higher risk of stroke with atrial fibrillation. The first symptom they might present with might be a stroke, instead of symptoms of a rapid heart rate."

Many ways to treat cardiac arrhythmias (with caveats)

Treatment of the cardiac arrhythmias that occur in MMD1 also poses some special challenges. For example, there are several medications used in the general population to treat arrhythmias that may be dangerous in people with MMD.

Drugs known as beta blockers, which have indirect effects on arrhythmias, and more potent anti-arrhythmic drugs, such as amiodarone (Cordarone) or sotalol (Betapace, Sotalex, Sotacor), are sometimes prescribed for people with MMD, Groh says. However, he worries about this.

"One of the problems with those medications is that they all have the potential for making conduction disease worse" because they dampen the transmission of electrical signals in the heart, Groh cautions.

In general, he says, if someone with MMD “has symptomatic arrhythmias, and they’re going to be treated with one of these anti-arrhythmic drugs, they should have either a pacemaker or a defibrillator in place to protect them from the worst rhythm disturbances, which could be life-threatening.”

If the source of the rhythm disturbance can be pinpointed, a technique called ablation (destruction of tissue by heat or cold) can sometimes solve the problem. In this procedure, a catheter — the “ablator” — is introduced into the heart, usually through a vein.

This type of intervention is particularly useful in a type of fast arrhythmia to which people with MMD1 are prone, Groh says. In this type of abnormal heart rhythm, the conduction of impulses through the heart is slowed so much that the electrical impulses loop around and re-enter the tissue, paradoxically leading to a heart rhythm that’s too fast. "Conduction is so slow that the tissue becomes excitable again and allows the impulse to re-enter," says Groh. The ablation procedure destroys the re-entry loop.

When it comes to electronic devices, Groh’s research has led him to believe that an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), which can protect against both slow and fast arrhythmias, may be better than a pacemaker, which protects only against slow arrhythmias. (All defibrillators have a backup pacemaker.)

Although the superiority of ICDs over pacemakers in MMD is suggested by his research, it needs to be confirmed in a trial comparing the two interventions, he says. "In our study, nearly half the patients that had pacemakers died during the follow-up period. A significant percentage of that population had sudden, unexpected death, and I think that speaks to the protection that the defibrillator can give over the pacemaker."

Decisions about devices: To prevent or treat?

Ultimately, decisions about treatment, including the use of potentially lifesaving devices, rests with the individual with MMD — or on occasion, a parent or guardian (although it’s very rare for children with MMD1 to have significant heart involvement).

Some people are eager to receive a device as a preventive measure, even if the degree of fibrosis or arrhythmia isn’t yet severe enough to cause problems. Others reject the idea, and Groh respects that choice as well.

"Some of my patients, after I explain this to them, say to me, 'Dr. Groh, you’ve gone through this with me, and I’ve decided that I only want a pacemaker or defibrillator if it’s absolutely necessary right now; I don’t want a prophylactic pacemaker or defibrillator.'"

That, however, doesn’t mean they should ignore their hearts. Groh would like to establish an online cardiac resource for people with MMD. "I’d like to set up a website that will provide further information to patients and physicians, one that would allow EKGs to be put on the website so we could review them. This is something I’d really like to do in the future."

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information