Physical Therapy: Flexibility, Fitness and Fun

Say "physical therapy" and most people think of World War II movies with wounded heroes struggling with weights and pulleys, athletes nursing injuries in whirlpool baths, and heart attack survivors sweating on treadmills.

Say "physical therapy" and "muscular dystrophy" in the same sentence and you may get the same uncertainty from anxious parents that you do from skeptical insurance company representatives.

"Does it really help in those diseases?" is a frequent response. "I mean, what can you do in a degenerative, genetic disease?"

"Does it really help in those diseases?" is a frequent response. "I mean, what can you do in a degenerative, genetic disease?"

That's what Yvonne Nichols of Horseheads, N.Y., heard from her insurance company when she tried to get physical therapy last summer for her 8-year-old son, Scott, who has Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

"The insurance company termed the therapy 'inactive care,'" Nichols says. "They call it inactive care when it's not going to improve a condition, and they refused to cover it."

Fortunately for Nichols, she and Scott live in an area where the schools are very good about complying with the requirements of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which mandates that every child is entitled to a full education, including physical education, with whatever special services and adaptive equipment may be necessary to make that happen (see in "Getting Started with Physical Therapy" section below).

Scott's DMD was diagnosed in kindergarten, when his physical education teacher noticed that his motor skills weren't developing as expected and encouraged the family to investigate.

That summer, after the diagnosis, Nichols swung into action. "We went through the Committee on Special Education," she says. "I contacted the school, because I had a friend who had a son with behavioral problems. They went through the CSE, so I knew a little about it and what to do."

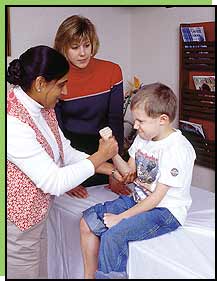

Scott was classified as "orthopedically impaired" and assigned to a physical therapy program involving a half-hour of therapy two days a week during the school day. The therapy mostly involves stretching his heel cords and the muscles at the backs of his thighs, but Scott is also learning to manage his energy level and stay safe. There's some fun involved, too, like walking on 4-inch stilts.

"I've heard about red tape with the CSE," Nichols says, "but we had no trouble whatsoever. We've had nothing but good experiences."

A new way to look at PT

"In the old way of looking at things, rehabilitation meant you were going to get better," says Sheila Hayes, a physical therapist associated with the MDA/ALS Center at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York.

That's no longer the case, she says. In fact, the American Physical Therapy Association recently started a special section on degenerative diseases.

Shree Pandya is a physical therapist and educator who's been involved with the MDA clinic at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) for many years. Nowadays, she works mostly with patients - including Scott Nichols - who've been in research studies at the university.

Shree Pandya is a physical therapist and educator who's been involved with the MDA clinic at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) for many years. Nowadays, she works mostly with patients - including Scott Nichols - who've been in research studies at the university.

Pandya sees physical therapy as "helping people to remain at their highest functional level possible at any given point in time within the constraints of their disorder."

Physical therapy overlaps a great deal with occupational therapy, but there are some differences. For the most part, although both disciplines deal with maximizing function, OT is concerned more with the small muscles, particularly those of the hands, while PT is concerned more with large muscles, such as the legs, and with mobility.

Today, physical therapy is an integral part of the treatment of almost any neuromuscular condition and is usually included in the medical plan for everyone with these conditions and in the school or preschool program for children.

How much and what kind?

Unfortunately, there's a lack of research on exactly what kind of PT and how much is ideal in each of the various neuromuscular disorders.

Most therapists agree that a certain amount of stretching and range-of-motion exercises (these ROMs keep joints supple by putting them through their normal range of motion in space) is almost always a good idea in neuromuscular diseases. Such maneuvers tend to slow down or sometimes even prevent the development of contractures, the freezing of joints that aren't moved.

Most therapists also agree that a certain amount of exercise is good for cardiovascular health, and that some weight bearing, where possible, can head off the development of the bone-weakening disorder osteoporosis. Most also agree that strenuous exercise in certain types of metabolic muscle disorders (for example, phosphorylase deficiency, or McArdle's disease) can lead to serious muscle damage and perhaps kidney damage as well. (This is because proteins leaking out of damaged muscle cells reach the kidneys, where they're toxic.)

In periodic paralysis, attacks of paralysis are often brought on by resting after strenuous exercise. Cramping of muscles, paralysis of muscles or cola-colored urine are warning signs to stop exercising immediately in any muscle disorder.

In periodic paralysis, attacks of paralysis are often brought on by resting after strenuous exercise. Cramping of muscles, paralysis of muscles or cola-colored urine are warning signs to stop exercising immediately in any muscle disorder.

For some people, just activities of daily living, like walking up and down a few stairs, getting in and out of chairs, and turning from side to side in bed have to suffice for physical therapy. Even those simple things can help preserve both strength and flexibility.

But when it comes to more concerted efforts to increase strength or muscle bulk in the muscular dystrophies, disagreements and uncertainty surface.

Several of the dystrophies (Duchenne, Becker, some limb-girdle dystrophies and at least one congenital dystrophy) are known to result from fragile muscle membranes. These membranes are sheaths that surround each muscle fiber (long cell) inside the muscles. In several muscular dystrophies, the sheath is weakened because it lacks one of several membrane proteins. Extra stress on the membranes, many experts have reasoned, may hasten muscle degeneration.

On the other hand, muscles are designed to be stressed, and leaving them alone can also hasten their deterioration and interfere with overall fitness.

Pandya, despite many years of experience in the field, isn't sure about the exercise question. "I would rather be cautious," she says, "but sometimes I wonder if we have been too cautious." She says the most serious quandaries are posed by "college-age kids with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy or limb-girdle dystrophy, who do not have as much of a progressive disorder as Duchenne dystrophy and are into exercise with weights and equipment."

Pandya prefers that they do walking or swimming instead of weight lifting, but she says there aren't a lot of studies. "Basically we try to summarize what we know from the literature, that a certain amount of exercise is good for all of us, as well as keeping weight down, eating a healthy diet, all those things." She's not enthusiastic about exercises that may tear membranes and damage muscles cells that have a hard time renewing themselves (which describes muscles in muscular dystrophy).

She recalls a research study on boys with DMD conducted many years ago. Exercising the thigh muscles three times a week temporarily strengthened these muscles, but when the children were tested six months and a year later, they had lost the gains.

Because of this study and others, Pandya isn't keen on overzealous strengthening exercises in severe muscular dystrophies like DMD. She's more interested in increasing the child's overall flexibility. Of equal concern to Pandya is a youngster's experience of childhood.

"The child has to be a child first and a child with muscular dystrophy next," she says, and she tries to build a PT program around that philosophy.

Don't overdo it

Jenny Robison, a physical therapist who's long been associated with the MDA clinic at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., has much the same philosophy.

"I try not to overload my patients," she says. "But in my years of experience, I can see kids whose parents have done exercises and night splints [to keep feet in proper alignment] and surgeries, and they're in so much better shape than kids who haven't had any intervention. I think it works, but it's a lot to do." Physical therapy "prevents or slows down problems like contractures and keeps people in a better functional position to do things that they want to do, to live life as well as they can. It also helps people by getting them the right equipment," Robison says.

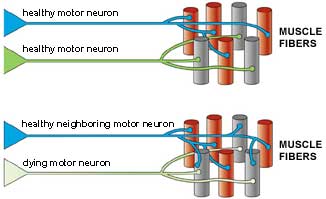

Concerns about exercise also exist in motor neuron disorders like spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

In these disorders, motor neurons, the nerve cells that control muscle movement, are lost, leaving muscle fibers "orphaned" - without a nerve supply. Some investigation of exercise in motor neuron disorders has been done, Hayes says, and the consensus is this: When motor neurons die or don't function, their neighboring motor neurons can take over, at least for a while, supplying more than their share of muscle fibers with nerve signals. But these new connections are fragile and under stress. Overexercising the muscles can stress the new connections still further, perhaps hastening damage (Hayes doesn't think this is likely), but almost certainly making it harder for a person to function by the next day.

Hayes' recent experience is with ALS patients, but she says conclusions about exercise in ALS should apply equally to people with SMA.

In her view and that of other experts in motor neuron disease physical therapy, she says: "It's OK to do moderate strengthening for muscles that are uninvolved, that show no overt weakness. But once a person is starting to exhibit weakness, it's best to stay away from weight machines, free weights or any type of resistance exercises. If the goal is to improve function, then exercising to the point where muscle fatigue impairs function is counterproductive."

A child first

Children especially need to have a PT program that works for them in the context of their other activities. No one understands Pandya's message about children needing to be children first better than Sherrie Shannon of Fairview, Pa. Her son, Christopher, an 11-year-old with DMD, has had the wrong kind of physical therapy, and too much of it, she says.

Children especially need to have a PT program that works for them in the context of their other activities. No one understands Pandya's message about children needing to be children first better than Sherrie Shannon of Fairview, Pa. Her son, Christopher, an 11-year-old with DMD, has had the wrong kind of physical therapy, and too much of it, she says.

Shannon says she was directed to a physical therapist in her area who was approved by Medicaid but knew next to nothing about MD.

"Christopher was only the second kid with muscular dystrophy that she had ever seen," Shannon says, adding that the therapist told her she'd had only about four hours of education on neuromuscular disorders in her five years of PT training.

"She started him on wall squats - where you lean against the wall and squat down and have to get back up - and on sit-ups," Shannon recalls. Christopher has recently begun a pool therapy program, a welcome change, but Shannon says of the therapist, "She's not listening for Christopher's cues saying 'I'm tired.'"

Shannon describes her son's schedule: "From 7:30 to 8 in the morning, he does leg exercises and manual stretches at home; then at a quarter to 9 he gets more stretches at school, at 12:30 more stretches, more when he gets off the bus and then again before bed. On the days when he has PT after school, he goes from school to therapy."

Shannon is all for the stretches - in moderation - and for flexibility exercises in general, but, she says, "I don't see that strengthening has helped him in any way, because he's still declining at an average rate." Fortunately, Shannon has recently been able to bring in a consulting therapist with years of experience in DMD who's been helping their primary therapist. Christopher's program is undergoing modifications and shifting more toward water therapy.

But Shannon is also concerned with the quality of Christopher's life. She describes how the physical therapist had him doing an exercise called "side-lying subluxation - where he lies on his side and has to lift his leg and kick behind him. That's supposed to help strengthen the muscles that bend the hip." Shannon says, "You can do that standing, doing kickball. I'd rather let him kick the ball."

Christopher also likes sled hockey, a game his mother describes this way: "He sits down in a sled, someone pushes him, and he hits the puck." Winners on Wheels, a program she found through her MDA office, sponsors sled hockey in her area.

Nowadays, when Christopher asks if he can play instead of doing exercises, Shannon tells him, "We'll wait a half-hour for the exercises. Go play."

Tapping into technology

PT isn't just about exercises. It's also about technology and modifying the environment. Canes, walkers, wheelchairs, scooters, neck supports, and ankle-foot and knee-ankle-foot orthoses (AFOs and KAFOs) are among the more common devices used in neuromuscular conditions.

PT isn't just about exercises. It's also about technology and modifying the environment. Canes, walkers, wheelchairs, scooters, neck supports, and ankle-foot and knee-ankle-foot orthoses (AFOs and KAFOs) are among the more common devices used in neuromuscular conditions.

But sometimes modifying an armchair so that it has more support or constructing a way to hold a book at eye level can make an enormous difference to someone's physical well-being.

"A therapist can try various devices and see what works the best," Hayes says. "ALS patients are a challenge, because some of the assistive devices have to be modified if they have hand weakness. You may have to put forearm platforms on a walker, for example. There's a lot of equipment available; you just have to know what to try with each patient."

And, says Hayes, you have to be alert to changes in the patient's condition, a common factor in neuromuscular disorders.

A popular intervention in many conditions is the AFO. AFOs are typically constructed out of molded plastic, with a support that goes up the calf and continues under the sole of the foot. The AFO holds the foot in a functional position, preventing "foot drop" (the foot flopping down because of weakness in lifting it) and slowing the development of contractures at the ankle joint.

Pandya says she calls AFOs night splints when she's thinking about DMD, because in this disease they're more often used to prevent contractures than to aid walking and are worn overnight for this purpose. (Pandya says she thinks they probably aren't needed if the boys are still standing several hours a day and if the parents and child are willing to do regular stretching exercises.)

In other conditions, such as myotonic muscular dystrophy (MMD), they're used to aid walking by preventing foot drop, Pandya says.

Pandya and Robison are both involved in the prescription of wheelchairs and other mobility devices and in the particulars of their modifications and seating. Robison has a special certification in wheelchair seating from the Rehabilitation Engineering Society of North America, but even without special credentials, wheelchair seating and modification is an area that falls squarely in the physical therapist's domain.

A scooter may be fun to "zip around in" for the person with ALS who isn't too far along in his disease, Hayes says, but therapist and patient have to be realistic: The person is likely to need the more complete support of a wheelchair in time, and his insurance isn't going to be thrilled about paying for two expensive devices within a few years of each other.

In DMD, Pandya says, she likes to see a child start with a lightweight, flexible wheelchair that's relatively inexpensive and easy for everyone to maneuver.

In fact, she says, some children can push it themselves with their remaining arm strength, which is good exercise. Then, in high school, when the child has reached his full size, she recommends getting a power wheelchair for maximum mobility. By then, weakness usually mandates its full-time use. Pandya is also conscious of insurance restrictions and says the companies aren't going to pay for too many vehicles in too short a time.

Specialized knowledge

Finding a physical therapist these days is fairly easy. But finding one with the specialized knowledge it takes to treat the problems in neuromuscular disorders and one that an insurance company or government health plan (such as Medicare or Medicaid) will cover is another story.

The MDA clinic is a good place to get a referral to a therapist who knows about neuromuscular disorders and to set up a free yearly consultation with one.

But insurance or personal resources are required to finance an ongoing therapy program that's not connected to a school or early childhood program, and that's where the going can get tough. MDA clinic physicians can help you appeal to insurers regarding the need for a therapist who specializes in neuromuscular conditions.

Financial concerns aside, finding the ideal person is doubly difficult if you don't live near a big city, Robison says. The American Physical Therapy Association (see "Getting Started" section below) may be able to help you find a specialist in your area. Where children are concerned and you can't find someone with neuromuscular disease expertise, Robison advises parents to search for a pediatric physical therapist.

Yvonne Nichols advises parents who are searching for a physical therapist: "It's important that it's a physical therapist that the child likes. They talk and joke together, and they need to do that. Scott is not demonstrative in any way, but he runs through the clinic and hugs Shree." (Scott sees Shree Pandya for evaluations as part of a drug study.) She says he also loved the private pediatric therapist the family was temporarily able to see.

Schools can be a good source of help and advice, Robison says, but you have to be on your guard. "Some schools are great and some will do as little as they have to do. Some of these schools will run you over if you don't learn to fight for yourself."

Robison strongly endorses parent advocacy groups that interpret disability law for families and help them make school systems comply with regulations.

Social workers associated with medical centers or school systems can also be a help. "The more informed parents are the better they can advocate for the child," Robison says.

Robison and Pandya see the role of the physical therapist as more of a consultant to the parents and the school staff than as someone who necessarily does hands-on therapy during the school day (although sometimes they do conduct therapy sessions this way).

"Therapists in the schools can act as a bridge between us [at university medical centers] and the school and parents and help the school staff understand the changes in function and how to handle the child," Robison says.

"Occupational and physical therapists in the school system are important," she says, but these days, they're usually "more in a consulting role in the school system, usually not in a direct therapy role. "They can be an advocate for the child in the school system, because they understand the disease and the equipment. They can go to the principal and say why he really needs to have a computer. They're a medical bridge to the school."

For children under 3 who aren't yet in regular school programs, state-administered, federally mandated programs, generally called early intervention for children under 3, and preschool education programs for children 3 to 5, are part of IDEA. Therapies can be conducted in the home, preschool, daycare center or other settings. Such programs "help with equipment, with therapy, with getting the right things for children," Robison says.

Getting Started with Physical Therapy

Getting started with a physical therapist can take some work on your part, but it's worth the time and effort to improve your or your child's quality of life.

One way to find a therapist in your area is through the American Physical Therapy Association in Alexandria, Va., which maintains a state-by-state listing of certified therapists with specialties. Call (800) 999-2782 or visit www.apta.org.

One way to find a therapist in your area is through the American Physical Therapy Association in Alexandria, Va., which maintains a state-by-state listing of certified therapists with specialties. Call (800) 999-2782 or visit www.apta.org.

Help from MDA

Your MDA clinic is always a good place to start with physical therapy. MDA covers one visit with a therapist a year, designed to help you set up a home physical therapy program or work with a community or school-based therapist. These therapists are knowledgeable about neuromuscular disorders and can serve as consultants for local therapists, teachers and families.

MDA also covers some of the expenses associated with leg braces (orthoses) and wheelchairs. Call your local MDA office, the national office at (800) 572-1717, or visit MDA's Web site at www.mda.org for details about MDA's programs.

Government, schools and other agencies

Prior to the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in 1975, most children with serious disabilities were shut out of public education. The IDEA of 1975 was significantly amended in 1997, and today it's a comprehensive federal program, administered separately by each state, designed to provide a "free, appropriate public education" to every student regardless of disability.

The law now covers infants and preschool children as well, on the theory that what happens before school starts has a major influence on educational success.

Services judged necessary for a student to take full advantage of the educational system, even if they're primarily "medical" in nature, such as physical therapy, can be included in a child's IEP, the individualized education program that each school system sets up for a child with a disability.

For more information about the IDEA, see the Web site at www.ed.gov/offices/OSERS/IDEA.

To set up an IEP, you can contact your local school district, usually working through a Committee on Special Education. Call your local school and speak to the principal or the person in charge of special education. If you don't have success (or even if you do), you may want to involve yourself in a parent advocacy group.

A list of parent advocacy groups, usually called parent training and information programs, can be found for each state on the Web site of the National Parent Network on Disabilities (NPND). You can call NPND at (202) 463-2299 or e-mail NPND@cs.net.

A program for an infant with a disability is known as an individualized family service plan (IFSP). To set up an IFSP, contact the agency in your state that's in charge of early intervention services for infants and toddlers with special needs. Therapists, social workers, pediatricians and support groups can help direct you to the right agency.

You can also find information through the National Information Center for Children and Youth with Disabilities, a clearinghouse for information and referrals on disability-related issues for children and youth from birth to age 22. Contact NICHCY at (800) 695-0285 or nichcy@aed.org, or visit www.nichcy.org. For lists of agencies in your state, visit the State Resource Sheets section at mda.org.

Taking to the Water

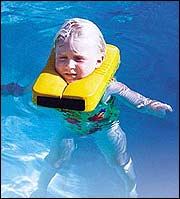

"Swimming is probably the most important thing responsible for the condition I'm in," says Chad O'Connell, who's 26 and has Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

"Swimming is probably the most important thing responsible for the condition I'm in," says Chad O'Connell, who's 26 and has Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Unlike many people of his age with DMD, says O'Connell, he doesn't need a ventilator, has fairly good cardiac function, and has kept his weight down despite using prednisone, a drug that almost always causes significant weight gain. He attributes all this to his time in the water.

"I'm probably one of the strongest people with DMD that I know. I'm stronger than people that are 18 years old," he says.

O'Connell remembers taking a bus to a pool near his elementary school in Fairport, N.Y., as part of the school day. Then, starting in ninth grade, he attended schools that had pools.

The swimming was considered adapted physical education, something that's required by the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act. O'Connell also had some physical therapy through his school system.

The swimming was considered adapted physical education, something that's required by the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act. O'Connell also had some physical therapy through his school system.

"I still think swimming is the best," he says of the various physical education and physical therapy activities he's done. "I pace myself. I don't try to overdo it."

Shree Pandya, a physical therapist at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center who has evaluated O'Connell as part of a drug study, couldn't agree more with O'Connell's assessment of his swimming program. "What we have always recommended here as one of the best exercises is swimming," Pandya says.

"That's because it's fun for the kids and they can exercise all the muscles in the body at the same time. They can even throw in some pulmonary work, like holding the breath and blowing bubbles in the water. "Water is a medium in which they can function even in the late stages of a neuromuscular disease. I've had kids who can't walk who still can go in the water and swim or walk in the pool. While they're losing other activities, this is an activity they can stay with.

"Even a child who doesn't have the strength to function on land will be able to function in the water, because the buoyancy of the water can be used to minimize weight and the effect of gravity," she says. "You can use water as a medium of assistance or resistance, depending on what movement you're doing and how you do it."

Family fun

Cheri Gunvalson and her family live in Gonvick, Minn., where it's too cold to swim outside most of the year. Her son Jacob, 8, has Becker muscular dystrophy.

"I think swimming is one of the best activities for Jacob," Gunvalson says. "We swim at a local pool at a motel. It has a warm whirlpool, too, and he's thin and gets cold fast, so then he can go in the whirlpool. The cost is usually $2 to $3 per time. I bring all three of my kids and they play together. Our local pool is an outdoor one that's only available three months a year, so the motel pool works well."

"I think swimming is one of the best activities for Jacob," Gunvalson says. "We swim at a local pool at a motel. It has a warm whirlpool, too, and he's thin and gets cold fast, so then he can go in the whirlpool. The cost is usually $2 to $3 per time. I bring all three of my kids and they play together. Our local pool is an outdoor one that's only available three months a year, so the motel pool works well."

Pandya, located in upstate New York, says they, too, are "talking indoor pools." She says, "We really push for swimming in community pools. We have two or three pools that are available, with nominal charges."

Safety first

Of course, take sensible precautions. Make sure an able-bodied person is at the pool at all times in case something goes wrong, and make sure there are no heart problems that would rule out swimming.

Special problems occur in cold temperatures (including cold water) in some disorders. In periodic paralysis, cold can bring on an attack of paralysis, while in myotonic dystrophy (MMD) and paramyotonia congenita (PC), cold water can cause muscles to stiffen and interfere with swimming. People with these conditions should swim in warm water.

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information